- Home

- Josephine W. Johnson

Now in November

Now in November Read online

NOW IN

NOVEMBER

Josephine Johnson

Afterword by Nancy Hoffman

Published in 1991 by the Feminist Press at the City University of New York

The Graduate Center, 365 Fifth Avenue, Suite 5406

New York, NY 10016

feministpress.org

Copyright © 1934, 1962 by Josephine Johnson

Afterword copyright © 1991 by Nancy Hoffman

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or used, stored in any information retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the Feminist Press at the City University of New York except in case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johnson, Josephine Winslow, 1910–1990

Now in November / by Josephine Winslow Johnson ; afterword by Nancy Hoffman

p. cm.

Previously published: New York, Simon & Schuster, 1934.

I. Title

PS3519.02633N6 1991

813′.52—dc20

90-26975

eISBN 978-155861-730-8

This publication is made possible, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.Cover Page

2.Title Page

3.Copyright page

4.Part One: Prelude and Spring

5.Chapter One

6.Chapter Two

7.Chapter Three

8.Chapter Four

9.Chapter Five

10.Chapter Six

11.Chapter Seven

12.Chapter Eight

13.Chapter Nine

14.Chapter Ten

15.Chapter Eleven

16.Chapter Twelve

17.Chapter Thirteen

18.Chapter Fourteen

19.Chapter Fifteen

20.Chapter Sixteen

21.Chapter Seventeen

22.Chapter Eighteen

23.Part Two: The Long Drouth

24.Chapter One

25.Chapter Two

26.Chapter Three

27.Chapter Four

28.Chapter Five

29.Chapter Six

30.Chapter Seven

31.Chapter Eight

32.Chapter Nine

33.Chapter Ten

34.Chapter Eleven

35.Chapter Twelve

36.Chapter Thirteen

37.Chapter Fourteen

38.Chapter Fifteen

39.Chapter Sixteen

40.Chapter Seventeen

41.Chapter Eighteen

42.Chapter Nineteen

43.Part Three: Year’s End

44.Chapter One

45.Chapter Two

46.Chapter Three

47.Chapter Four

48.Chapter Five

49.Chapter Six

50.Chapter Seven

51.Afterword

52.Notes

53.About the Author

54.About the Feminist Press

55.Also Available from the Feminist Press

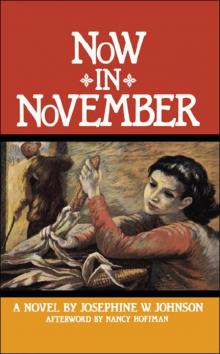

Josephine Johnson at the time she wrote Now in November. From the private collection of the family of Josephine Johnson.

NOW IN

NOVEMBER

PART ONEPRELUDE AND SPRING

1

NOW in November I can see our years as a whole. This autumn is like both an end and a beginning to our lives, and those days which seemed confused with the blur of all things too near and too familiar are clear and strange now. It has been a long year, longer and more full of meaning than all those ten years that went before it. There were nights when I felt that we were moving toward some awful and hopeless hour, but when that hour came it was broken up and confused because we were too near, and I did not even quite realize that it had come.

I can look back now and see the days as one looking down on things past, and they have more shape and meaning than before. But nothing is really finished or left behind forever.

The years were all alike and blurred into one another, and the mind is a sort of sieve or quicksand, but I remember the day we came and the months afterward well enough. Too well. The roots of our life, struck in back there that March, have a queer resemblance to their branches.

The hills were bare then and swept of winter leaves, but the orchards had a living look. They were stained with the red ink of their sap and the bark tight around them as though too small to hold the new life of coming leaves. It was an old place and the land had been owned by Haldmarnes since the Civil War, but when we came no one had been living there for years. Only tenant farmers had stayed awhile and left. The land was stony, but with promise, and sheep grew fat in the pastures where rock ledges were worn back, white like stone teeth bared to frost. There were these great orchards planted up and down the hills, and when Mother saw them that first day she thought of having to gather the crop and haul the apples up this steepness, but she only said a good harvest ought to come, and the trees looked strong though old. “No market even if they bear,” I remember Father said; and then,—“it’s mortgaged land.”

Nobody answered, and the wagon went on groaning and squeaking in the ruts. Merle and I watched the jays, blue-flickering through the branches, and heard their screams. The elms were thick with buds and brown-webbed across the sky. It was beautiful and barren in the pastures, and the walnuts made a kind of lavender-colored shadow, very clean. Things were strange and unrelated and made no pattern that a person could trace easily. Here was the land and the spring air full of snow melting, and yet the beginning of fear already,—this mortgage, and Father consumed in himself with sour irritation and the future dread. But Mother sat there very quiet. He had not told her the place was mortgaged, and the land at least, she had thought, was unencumbered, and sanctuary though everything else was gone. But even in the moment when she saw that this, too, was uncertain and shifting ground, something she always had—something I didn’t know then and may never know—let her take it quietly. A sort of inner well of peace. Faith I guess it was. She stood a great deal and put up with much, but all without doubt or bitterness; and that she was there, believing and not shaken, or not seeming so at least, was all that we needed then to know. We could forget for the time this sense of impermanence and doubt which had come up from his words. Merle was ten then and I was fourteen, and it seemed to us that some great adventure had begun. But Father looked only at the old, year-rotted barns.

He wasn’t a man made for a farmer, Arnold Haldmarne, although brought up on the land when a boy, and now returning to acres not different much from the ones he used to plough. He hadn’t the resignation that a farmer has to have,—that resignation which knows how little use to hope or hate, or pray for even a bean before its appointed time. He’d left the land when he was still sixteen and gone to Boone, making himself a place in the lumber factories there. He’d saved and come up hard and slow like an oak or ash that grows with effort but is worth much more than any poplar shooting two feet high in a season. But now he was chopped back down to root again. It’s a queer experience for a man to go through, to work years for security and peace, and then in a few months’ time have it all dissolve into nothing; to feel the strange blankness and dark of being neither wanted nor necessary any more. Things had come slow to him and gone fast, and it made him suspicious even of the land.

We hauled our beds here in the wagon with us. The car was sold and most of the furniture gone too. We left our other life behind us as if it had not been. Only the part that was of and in us, the things we’d read and the t

hings remembered, came with us, and the books we’d gathered through three generations but could not sell because earth was knee-deep and wading in books already. We left a world all wrong, confused, and shouting at itself, and came here to one that was no less hard and no less ready to thwart a man or cast him out, but gave him something, at least, in return. Which was more than the other one would do.

The house was old even then, not log, but boards up and down as barns are made. It was overgrown with the trumpet and wild red ivy-vines, twisted and heavy on the porch. Wild grapes were black across the well in autumn and there was an arbor of tame ones over the pump. Father found an old thrush’s nest hunched up in the leafless vines and took it down so that Merle wouldn’t mistake it for a new nest in spring and keep waiting for birds that never came. She filled it full of round stones and kept it up on the mantelpiece, maybe because she thought that the fire would hatch stone birds,—I didn’t know. She was full of queer notions and things that never existed on earth. She seemed older sometimes than even Kerrin who was born five years ahead.

That first spring when everything was new to us I remember in two ways; one blurred with the worry and fear like a grey fog where Father was—a fog not always visible but there, and yet mixed with it this love we had for the land itself, changing and beautiful in a thousand ways each hour. I remember the second day we came was stormy with fist-big flakes of snow and a northwest wind that came down across the hills, rattling the windows until the panes were almost broken, and the snow smacked wet against the glass. We thought it an omen of what the winters here would be, but strangely it was not cold afterward, even with almost two feet of snow along the ground, and a wind that shook the hickories from branch to root and sent a trembling down through the oaks. Merle and I went down by a stony place in the woods where the rocks shelved out to make a fall, and saw the air-bubbles creeping under the ice, wriggling away with a quick and slippery dart like furtive tadpoles. Down near the crawfish shallows the slime ferns were green and fresh and the sun so hot that we walked with our coats swung open and stuffed our caps away. Much of everything, it seemed afterward, was like that beginning,—changing and so balanced between wind and sun that there was neither good nor evil that could be said to outweigh the other wholly. And even then we felt we had come to something both treacherous and kind, which could be trusted only to be inconstant, and would go its own way as though we were never born.

2

IT WAS cold that first March and the ploughing late, I remember. There are times out of those early years that I have never forgotten; words and days and things seen that lie in the mind like stone. Our lives went on without much event, and the things that happened rise up in the mind out of all proportion because of the sameness that lay around them. That first spring was like in a way to most that followed, but marked with a meaning of its own.

Kerrin complained of the raw coldness and the house was hard to keep warm enough, but I remember one day of God that came toward the last, when we lay down carefully on the grass so as not to smash the bluets, and smelled their spring-thin scent. The hills were a pale and smoky green that day, and all colors ran into and melted with each other, the red of crab branches dissolving down into lavender of shadows, but the apples had bark of bloody red and gold. We went up where the old barn was then, the one grey-shingled with sagging beams—that was in its age like a risen part of the earth itself. We ate our lunch there on the south side of its wall and sucked in the hot spring sun and the pale waterwashed blue along beyond the trees, and even Kerrin seemed less alien and odd. Dad had too much to do and could not waste his time in coming, for the getting enough to live on and eat was work sufficient itself, and if a man thought to put anything aside or to pile it up for another time, it kept his nose in the furrow and his hand on the plough even while he slept. Mother stayed back with him to eat, and we thought they were probably glad to be alone one meal at least, without all our eyes staring them up and down and noting the things they said, to remember and repeat should they ever at any time contradict themselves.

We sat on the hill and watched a bluebird searching the trees and along the fence posts, and could see a long way off into the bottom land where the creek was and the maples that followed the water, long-branched and bending down to its pools. There was a shrike in the crab branches and Kerrin said they were cruel things, impaling the field-mice and birds on locust thorns so that their feet stuck out stiff like little hands. I didn’t think they were cruel things though—only natural. They reminded me of Kerrin, but this I had sense not to say aloud.

“Dad’s birthday comes soon now,” Merle said. “He’ll be fifty-seven. We should have a party, I think.—With presents.” She got up slow and shaking herself like a shaggy thing, heavy with warm sun and the food. She stood up in front of us with a round grave face.

“Where’ll you get the money?” Kerrin asked. “I’ve got some, but you haven’t any. I bought a knife that I’m going to give him.”

I looked at Kerrin quick and jealous. “—Where’d you get money from?” I asked. I hadn’t remembered there was a birthday coming, or thought of a thing to give, and it made me angry at her.

“It’s mine, Marget. I earned it!” Kerrin shouted. “I suppose that you think I stole or borrowed!” She got up and glared down on me. She was dark all over her long thin face, and I think she hoped that I did suspect her—she wanted to feel accused of dark and secret things. I probed the earth into little holes and buried a dandelion head, embarrassed and half-afraid of what she might do to me. “I just wondered,” I said, “since nobody else has any.”

Kerrin drew herself stiff like a crane. Her eyes seemed almost to twitch when she got excited or thought that she had a right to be. “You ought to have shut your mouth before you talked. You don’t know anything anyway!” Her liddy eyes opened fierce. She was always making scenes.

Merle clasped her fat hands together. She was anxious and uneasy and dreaded these times more than any snake or ghost. “We ought to be going back,” she said. “Maybe it’s later than the dishes—”

Kerrin looked angry and defiant. “What if it is? Who cares? Maybe I’m not going back a while!” She kept breaking twigs in her skinny hands.

“Kerrin,” I said like a pompous fool, “it isn’t always the things we want that are given us to do.”

“Why don’t you do them then?” Kerrin sneered.

I didn’t have anything to say. I was afraid to start probing again about the knife. Nothing was changed, but the afternoon seemed cold and chilly. . . . Merle started off down the hill. She was always thinking of Mother having to do the work alone, and was always the first to start at whatever there was to be done. Something was in her, even then, that kept walking foot after foot down a straight path to some clear place, and I wished then, and still do, that there was something in me also that would march steadily in one road, instead of down here or there or somewhere else, the mind running a net of rabbit-paths that twisted and turned and doubled on themselves, pursued always by the hawk-shadow of doubt. But even though I despised myself, it seemed that earth was no less beautiful or less given to me in my littleness than to Merle who had twice as much of good in her. And it seemed unjust and strange, but would probably balance up some day.

I ran after her and Kerrin followed, not wanting to come or to stay alone. “What’ll you give him, Merle?” I asked. She looked red and proud, pleased to be questioned when she knew the answer. “I’m going to give him a box,” she said. “A big one for his nails and screws.”

“That’s wonderful,” I told her. “You can make partitions in it for the sizes, and stain it some.” But I didn’t see how she was going to do it at all.

“What’re you going to give him?” Kerrin asked me. “Everyone ought to have something anyway. It doesn’t have to be awfully much.”

“You’ll see,” I said. In my heart I didn’t think that it would be much. I wondered if maybe it wouldn’t be anything at all. I wasn’t much go

od at making things.

We went slow in the hot sun. Merle was quiet, thinking, I guess, of all the chickens whose nests still had to be filled, and of the lame one who broke all her eggs but wanted so steadfastly to hatch that it was pitiful, though Merle hated her stupidness and the egg-stuck, smelly hay. It was almost two, and it seemed as if doing nothing at all took up time faster and more unknowing of what it swallowed than work had ever done. We walked up the cow-path where the ground was dry and warm, and alongside the thistles coming up. We could see Dad ploughing again already and robins come down in the furrows but keeping a long way off from the plough. There was a blue-smoke smell from burning brush and a warm haze in the air. Merle walked first, round and with a clean skin, and her mouth full of the one left piece of bread, and her hair messed up and woolly in the back; and then I came, not looking comparable to much of anything, with a brown dress on and beggar-lice seeds in my stockings; and then Kerrin straggled along behind, acting as though she might leave us any minute. She had reddish hair cut off in a bang, and her arms like two flat laths hung down loose from her shoulders, but her face was much sharper and more interesting than ours. She was stronger, too, and thought she could plough if Father’d let her. But he thought that a girl could never learn how and would only mess the field. “You help your mother, girls,” he’d say. “You help your mother.” He hired a man to work for a while and Kerrin was angry, felt things pounding in her, impotent and suppressed, and was sullen and lowering as the young bulls are. “He thinks I can’t do anything!” she’d shout at Mother. “He treats me as if I were still two. Why don’t you do something about it? Why don’t you make him see?”

“He’ll see after a while,” Mother said. “I think he’ll see pretty soon.”

“Why don’t you tell him though?” Kerrin’d say. “Why do you always wait so long about everything? You treat him like he was God Himself!” She’d end that way each time and slam a door somewhere while we pretended not to hear and would go on with what we did, only sick and drawn inside with hate. And for Mother who took things hard and quiet and lived in the lives of other people as though they were her own, it was like being bruised inside each time. I’d hear her suggesting things to Father in a quiet and hesitating way, and if he were tired he would be angry, or if in the rare times when he was pleased about something—about Merle’s fat cheeks that seemed to glow in wind, or about some clever thing she had said—he would laugh but never agree at once or let her know she had changed his mind. It was hard for her to bring things up at the times when he was pleased or sitting down quietly, because he had so few of these intervals, and it seemed like torturing him. We would walk carefully, praying the moment to last longer, to stretch out into an hour, and sometimes Mother would let the chance go past for the sake of peace, although there was much that she felt unjust, and had pestilent worries of her own she would like to have burdened on him.

Now in November

Now in November